Health training is about to take a huge leap forward with the launch of a virtual learning laboratory that pools a huge amount of data and learning tools.

"The key virtue of the BEST Network is its potential to allow the sharing of resources across a wide range of institutions, enhancing all members’ educational goals. It’s big picture stuff."

Four Australian universities and a number of peak medical bodies have banded together to create a world-first model for healthcare education that allows students to access up-to-date knowledge using next-generation technology.

The $4.5 million Biomedical Education Skills and Training (BEST) Network, which was launched in October, is an intelligent online learning system that includes a cloud-based repository of learning tools and resources. It is built on the adaptive learning platform Smart Sparrow which was invented at the University of NSW and is used in hundreds of tertiary-level courses in Australia and the US.

“We’re talking about super interactive content that adapts to students as they go, based on their level of knowledge,” says Dr Dror Ben-Naim, chief executive of Smart Sparrow.

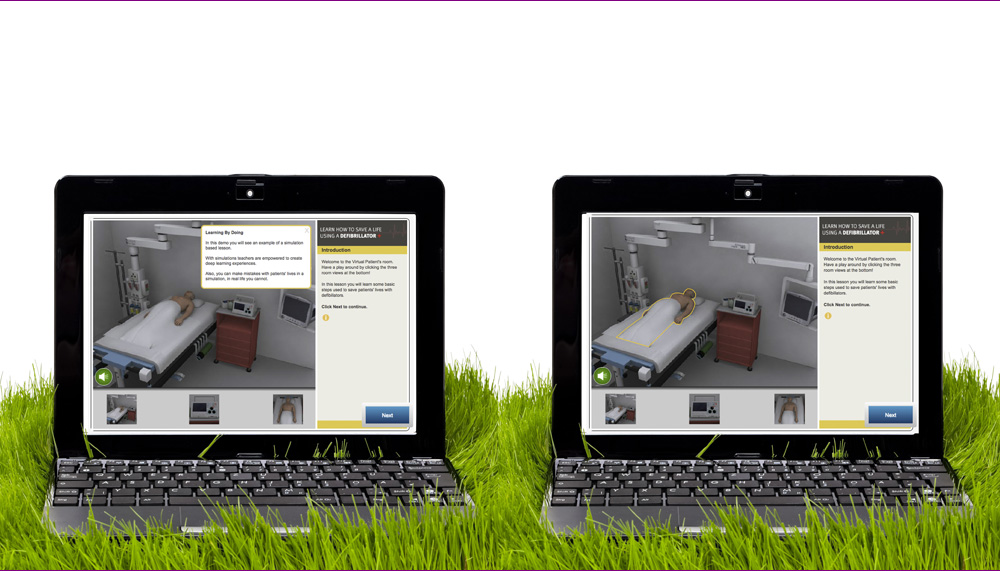

Until fairly recently, online learning was restricted to one-way videos, lectures and multiple-choice questionnaires. The BEST Network, however, allows for learning through exploring online worlds. Students take action in online medical cases and their actions shape the way the scenario unfolds. They proceed at their own rate and receive feedback as they progress.

The interactive learning experiences take place in virtual laboratories, with virtual patients and virtual microscopy, along with adaptive tutorials and smart medical cases, allowing for “learning by doing”. All manner of learning possibilities are created for staff and students of network members, a definite boon for smaller institutions that would previously have been handicapped due to constraints on funding and resources.

Mark Brown, associate professor of the School of Biomedical Science at the University of Queensland says the virtual laboratories (VLs) bring essential experience to students wherever they may be.

“Certain core skills are enhanced through doing. The VLs allow students to participate in learning experiences that would only normally be available in an on-campus laboratory setting,” Brown says.

Virtual dissecting rooms and patient clinics are included in the online world.

Ben-Naim says trials using virtual patients to train nurses in defibrillation at a hospital in Washington achieved a reduction in average response time from 1.4 minutes to 1.2 minutes; in a situation where seconds can make a difference, the technology is potentially life-saving.

UQ’s Brown says any core task, from measuring blood pressure to inserting an IV line, can be replicated in a VL, so that students and teachers can be trained in a wide variety of skills, as well as giving them feedback on group and individual performance.

Peter Smith, dean of medicine at the University of NSW says the information teachers receive from the program allows for a better understanding of how they are faring. “For example,” he says, “if there’s a cluster of students who’re getting the same thing wrong in the same way, we can go back and look at how we’re teaching it.”

In this way, teachers can evaluate students’ learning by watching how they react in real time.

The program can point students in the right direction if they make a mistake, so that the learning is tailored to the learner.

“There might be an anatomical picture of a limb and the program might ask you to name a nerve and a muscle,” Smith says. “If you get it wrong, it can tell you where to go to find the right answer.”

As students progress, activities are modified and results known instantly, while the program adapts to different levels of difficulty according to the student’s demonstrated ability.

Teachers are also able to construct or write their own lessons to target students’ strengths and weaknesses, Smith says.

By untethering learning from lecture theatres and laboratories, he says, health education will be moved to another level.

Content is created by accredited experts and learning specialists. Ben-Naim says a peer review process is built into the system due to its collaborative nature, ensuring that premium content is uploaded.

“BEST appears to be an excellent vehicle to bring extra learning to off-campus students wherever there are gaps in the curriculum,” he says.

The network is a combined effort of founding members, the University of NSW, the University of Queensland, the University of Melbourne, James Cook University, the Australia College of Nursing and peak medical bodies, and has already attracted international interest.

The University of Queensland became involved because it wanted to improve its standard of training in anatomy and physiology, Brown says.

Also available to students is SLICE, the world’s first medical image bank. Professionals such as top pathologists, nursing educators and anatomists can upload their own images of up to 10 gigabytes. Slides are scanned and uploaded to the cloud.

“In the past, nurses and other healthcare professionals didn’t have access to this type of content because it was closed up in laboratory cupboards in universities,” Ben-Naim says.

Brown says it is beneficial because medical teaching is highly reliant on the availability of both normal and pathological images. The international scope and ability for each user to add content to the images, such as annotations which can also be shared, are other positive outcomes, he says.

“In this way groups of academics, blind to university borders, come together to produce the best possible learning resources to benefit the widest possible number of students,” he says.

According to Ben-Naim, the BEST Network is not only levelling the playing field, but improving it by increasing the capabilities of every healthcare educational institution and saving them money and time, allowing for more face-to-face instruction in a more productive way.

A single institution embarking on a project like this alone would incur higher costs and produce fewer results than can be achieved through a collective effort. Ben-Naim says this allows universities to do more with less.

The ideal of equality of access is at the heart of the project. Smith says well-funded universities will be able to share their teaching resources making it an essentially democratic initiative.

Ben-Naim sees it as a breakthrough in healthcare education because it enables anyone to access premium content no matter where they live or how privileged, or disadvantaged, the institution.

“People who live in disadvantaged areas have access to the same educational experience and technology as the people who live in metropolitan centres,” he says.

It isn’t only regional and remote areas that will be able to use the potentially lifesaving medical resources and tools. Smith says the international scope of the technology means use of the network can extend to nursing or medical schools in developing countries.

“There’s absolutely no reason why a medical school in Cambodia or Africa couldn’t access the learning facilities that are online here,” he says, adding it is beneficial because these schools are usually fairly under-resourced in infrastructure and have outdated equipment and facilities.

He says these schools could engage with the state-of-the-art and up-to-date knowledge stored in the network.

The technology also provides equal access for professionals in regional and remote settings, and Smith hopes the network will be used for continuing professional development.

He says those who work in regulatory agencies could also use it in promoting workplace health and safety. “It’s applicable in a number of areas,” he says

Brown points to the great advantage of pooled resources. “I think the key virtue of the BEST Network is its potential to allow the sharing of resources across a wide range of institutions, enhancing all members’ educational goals,” he says. “It’s big picture stuff.”

The program has already garnered interest from leading international universities, such as Harvard, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

In 2012, a $1.2 million project involving Smart Sparrow was announced by Health Workforce Australia, involving the development of a virtual patient program for use in health training in NSW.

Do you have an idea for a story?Email [email protected]

Aged Care Insite Australia's number one aged care news source

Aged Care Insite Australia's number one aged care news source