Person-centred aged care design – how the experts do it

Over the course of our careers as architects there have been moments that stand out.

An incontinent resident able to independently use a toilet when it was made easier to find. A man happily making tea for a friend once he had a kitchen to use. Another man, once stuck in hospital because of his unpredictable aggression, finding some peace in a home with a garden, digging with the maintenance team.

These stories have common features. They involve aged care settings and creative care programs. They involve simple changes and design interventions that led to those individuals leading fuller lives.

Our practice, Constructive Dialogue Architects, aims to improve existing buildings and create new ones that improve people’s quality of life. We have increasingly focused on aged care homes, because we see the need and potential for better buildings.

In 2022, we were tasked with writing the National Aged Care Design Principles and Guidelines (the Guidelines) for the development of supportive environments as part of a team based at the University of Wollongong, NSW. Critical to this team was Dementia Training Australia, an organisation that could train aged care executives, care workers and design professionals on implementing the Guidelines.

The National Aged Care Design Principles and Guidelines as a tool for change

There is a large body of evidence that demonstrates how a well-designed environment enables people to be more independent, mobile, and social, despite the range of frailties and cognitive impairments that may have prompted their move into residential aged care.

Australia has a legacy of care homes developed over the past 50 years that do not reflect this evidence base, where staff and residents are often fighting against poor design, or constrained by out-of-date care models, because the building leads the way.

In writing the Guidelines, our primary objectives were to:

- Articulate why building design matters, relating it to quality of life and care delivery

- Bring together the evidence on what makes a practical difference

- Create a document that would show how to improve and build better homes.

One key influence during the development of the Guidelines was architect Paul Pholeros, who spent his life working to improve the health of First Nations people through the improvement of existing housing. When he died in 2016, 7,200 homes had been fixed, which led to direct, measurable health outcomes for those living in them, including fewer eye diseases, skin problems, and hospitalisations.

Paul’s approach to design focused on identifying and installing ‘health hardware’. These were the basic building elements needed to support healthy living practices, such as running water. Conversations with Paul led to an understanding of how this approach could be adapted to improving aged care environments.

The Guidelines can be thought of in terms of ‘health hardware.’ For example, provision of safe and interesting outdoor spaces that reduce stress and promote a multitude of health outcomes. Another is an accessible domestic kitchen that promotes retention of crucial basic skills and supports a better dining experience. A third involves strategies that reduce noise, leading to improved sleep outcomes and lower agitation among residents.

It is crucial that the building works with staff and residents – it’s a living organism.

The Guidelines brought together decades of international research in a clear and highly illustrated format to support organisations to assess their current buildings, identify improvements, and implement changes. The audience is broad – from care staff who change buildings every day as they work, providers who have the power to renovate or build better homes, and the designers employed to map out the changes.

Four Principles emerged to counter recurrent challenges for residents in care homes. Guidelines sit under each Principle that explain specific ways to address that challenge:

- Enable the Person

This Principle tackles a consistent set of issues that are commonly seen in all types of buildings, not just aged care homes, for instance it could be applied to transport hubs, libraries, hospitals, etc. To enable the person, we must consider how good design can reduce cognitive load, bolster orientation, and support comfort. - Cultivate a Home

The feeling of being ‘at home’ may seem ephemeral, but it can be broken down into critical elements, such as providing meaningful things to do, ensuring appropriate scale, and supporting the personalisation of individual rooms. - Access the Outdoors

We know that getting outdoors is fundamental to health and yet often the amount of time spent outdoors is reduced once someone moves into care. Outdoor spaces need to be safe, interesting and immediately accessible from living spaces to be effective. - Connect with Community

Remaining connected with family, friends and the wider community is essential for a person's ability to thrive whilst living in aged care. Bringing the community into the home, and integrating the home into the built environment can both help to reduce the stigma of ageing and benefit the whole community.

CASE STUDY 1 Nazareth Care Home: A new home to support the small household approach

Constructive Dialogue are working with the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth in Western Sydney on the new “Nazareth Aged Care Home" that will realise the Principles and Guidelines in full.

The Sisters have a clear missional imperative that drives their work, and their desire was to create a real home for residents, and also an efficient and pleasant place for staff to work. The brief was developed through workshops and conversations that focused on each of the Principles, tailoring the Guidelines to work with the specific approach of the organisation.

The Nazareth will be home to 60 people, living in four separate apartments over two levels, each with their own living, dining and domestic kitchen spaces.

The first Principle – Enable the Person – started with a simple layout in each apartment, with a domestic kitchen at its heart, no dead ends, and corridors leading to outdoor space. Staff doors are hidden and resident doors highlighted. The client preference for hard flooring has been balanced with acoustically absorbent ceiling panels. Decentralised storage keeps equipment close to use, but avoids clinical clutter.

The second Principle – Cultivate a Home – was core to the Sisters’ vision. Each apartment is to be private from its neighbour, so staff do not pass through one apartment to access another one. Each has its own front and back door, and its own private garden or deck. There is a commercial kitchen in a neighbouring building which will serve Nazareth, but each kitchen within the residences has its own pantry, dishwashing space, and induction cooktops for a state-of-the-art dining experience. Residents will be able to eat what they like, when they like, and engage in cooking and washing up to the degree they wish. This approach is well-evidenced to be better for residents’ health and wellbeing.

Principle 3 – Accessing the Outdoors – has been implemented throughout. Balcony spaces leading to bedrooms, connecting decks between living spaces, and generous terraces have been included. Sym Studio Landscape Architects has designed meaningful outdoor spaces, which are full of life and interest.

Finally, the building should Connect with Community – Principle 4. Spaces for residents outside the apartments are provided, such as a room for parties and performances with a sun deck. On the ground floor, the Plover Café (named after the site’s current residents) can be used by all, including those attending the church on the same site.

The result is a design that realises the mission of the Sisters, addresses key operational challenges (to reduce the load on staff), and integrates enabling design elements that provide the highest likelihood that a person living in the home can use retained abilities. The building is due to be completed in early 2026.

CASE STUDY 2 Banksia Villages: Improving an existing building to support a shift in model of care

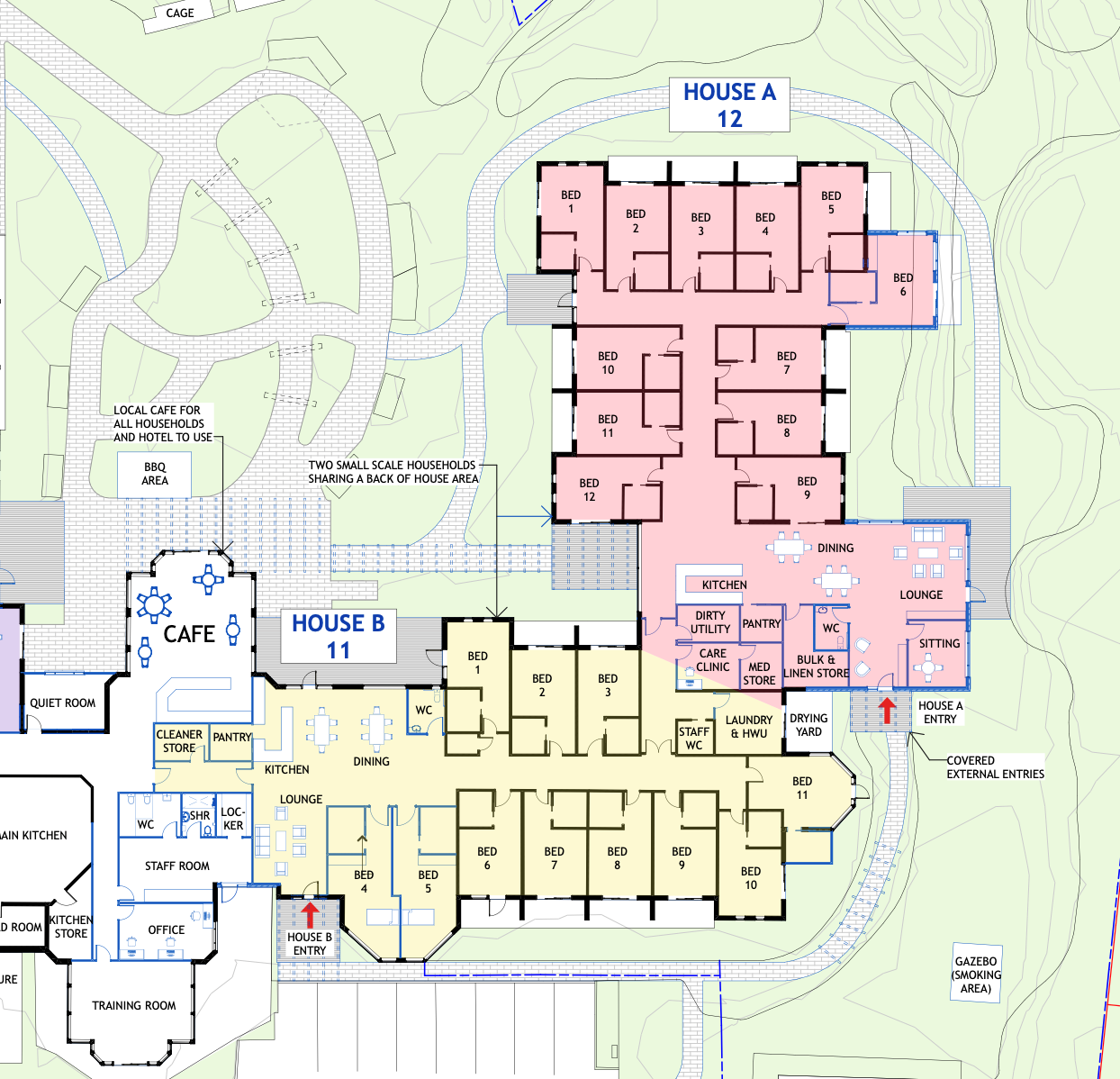

Banksia Villages, in Southern NSW, approached Constructive Dialogue at a time when they were considering a shift from larger scale living environments to smaller domestic settings. The development of their approach was supported by training delivered by Dementia Training Australia through funding from the Department of Health and Aged Care. A master plan was developed, and development funding was successfully sourced through the Department’s ACAR funding program (now known as the Aged Care Capital Assistance Program).

Similar to the Nazareth Care Home, the project brief was developed through workshopping the Banksia Villages model of care and the design elements required to support it. This included confirming how many people would live in a household, kitchen operations, and what was achievable in corridor reconfiguration to support residents' navigation.

As this project was about improving an existing environment, we audited the building and gardens to establish what was not working. This included assessing what would likely contribute to the increased use of gardens. The existing gardens are attractive but underused, with the design of the edge of the building identified as an issue. A key focus became Guidelines that addressed garden connections, verandahs, and clear paths.

The building work is currently underway and there is a realistic expectation that residents will consequently spend more time outdoors, contributing to better fitness, higher bone density, better sleep, and an improved quality of life.

The key to successful application of the Principles and Guidelines to refurbishment projects is establishing a small number of targeted changes, ones which have been assessed as having the greatest effect on residents’ lives. Once the construction is complete, the focus will shift to training staff how to make the most of the interventions, and to understand the design intent.

If the door is locked then no one will get out, but likewise if afternoon tea is set up on the verandah that is where people are likely to go.

The challenges are great, but the Principles and Guidelines support small and big steps to gradual change

Dementia Training Australia (DTA) is an invaluable resource for aged care providers. DTA's Environments Training Program is specifically designed to support aged care providers in understanding and applying the National Aged Care Design Principles and Guidelines.

This program goes beyond offering practical guidance for physical site improvements; it also aims to foster a cultural shift within organisations. By highlighting the profound impact of the built environment on people living with dementia, DTA’s training encourages a deeper recognition of how thoughtful design can enhance quality of life and care delivery.

Whether planning renovations, new builds, or operational adjustments, engaging with DTA can help embed meaningful and lasting change.

Nick Seemann is a co-author of the National Aged Care Design Principles and Guidelines. He is the managing director of Constructive Dialogue Architects and the environments specialist at Dementia Training Australia.

Liz Fuggle is an associate at Constructive Dialogue Architects, with over a decade of experience specialising in dementia design. She worked closely with aged care provider HammondCare on the development of their specialised Dementia Centre.

Email: [email protected]