The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality & Safety outlined 148 recommendations for improvement. This leaves little doubt we will see great improvements in the quality of care for clients and residents. One of the biggest areas we need to see improvements in is the capabilities of aged care workers to deliver emotional care.

Emotional care is by definition the capacity of aged care workers to facilitate healthy, pleasant emotions, and to help their clients and residents respond effectively to unpleasant emotions. It’s heavily dependent on emotional intelligence, our capacity to perceive, understand and respond to emotions rather than our IQ.

Aged care workers with high levels of emotional care generate trust with their clients and residents, and ensure they feel (more often than not), valued, cared for, consulted, informed and understood. It helps them bring out the best in clients and residents, to have them laughing and talking about who they are, and supporting one another. Friends and family also see and feel these benefits.

Emotional care is important for all people living in residential care, or with aged care services. However, it’s particularly important for people living with dementia.

The longer you live with dementia, the less reliant you become on your memory, logic and reasoning, and the more reliant you become on your feelings. People with dementia become more dependent on their emotional truth than what their logic tells them. Indeed, my mum, like almost all others living with dementia in residential care, is more a feeling being than a thinking being. As Dr David Sheard, founder of Dementia Care Matters says: “Feeling you matter is at the core of being a person, knowing you matter is at the heart of being alive, seeing you matter is at the centre of carrying on in life.”

For too long aged care providers have been relying on training that produces end of life and physical care competences such as cleaning, showering and toileting. These are highly important, but they are baseline, minimum and expected competencies. We need recruitment and training that gives us an aged care workforce competent and capable in emotional care.

We are at a stage of advancement with emotional intelligence, now in its fourth decade of existence. It should be used to help recruit and develop emotional care at scale, in the aged care sector. There are reliable and valid assessments that can be used to help recruit people with emotional intelligence. There are also training and development programs that can significantly improve emotional intelligence, by on average 17 per cent. These have been widely embraced by the corporate sector and now need to be more widely embraced in aged care.

For use in recruitment, there are good emotional intelligence assessments that come with a detailed technical manual.

This manual often includes peer-reviewed research publications supporting its reliability and validity (not just by the test author). It will also be easy to use and have clear reports for hiring managers detailing candidate scores. The market leaders also have great development-oriented reports for candidates who take the test. These reports help candidates identify how they could improve their emotional intelligence.

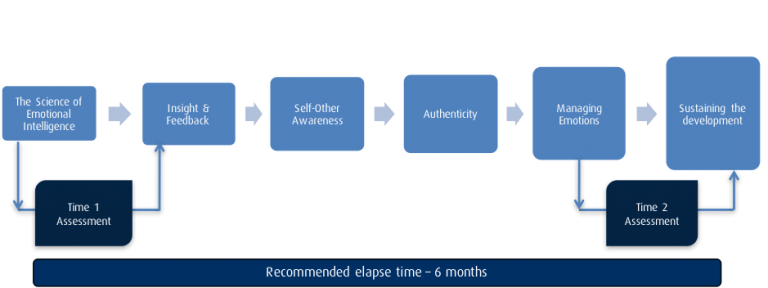

There are also great emotional intelligence development programs that can be delivered via one-on-one coaching, group webinar or traditional group classroom. They entail the following:

- a clear Purpose,

- expected Outcomes,

- an EI Assessment completed pre-program to create self-awareness and post-program to determine return on investment), and

- be in a learning journey format (e.g., a number of short 90 min to 2hr sessions over a period of 3-6 months).

This format allows people to then apply the models on the job and continue learning through practical application. Subsequent sessions should start with reflection and include a peer-coaching or mentoring component to help facilitate participant-led learning. Between sessions, participants are paired-up and asked to share their approaches and insights on how to apply the content. Below is an example of what an emotional intelligence development journey can look like.

One or two-day workshops can be great for introducing models and concepts, shifting mindsets and getting people to practise different approaches.

However, real behaviour change takes time, reflection, refinement and experiences from real-world application. This is why the journey format works best. If you are planning on designing one or two-day programs, ensure there is additional follow-up and support to maximise ROI.

One of the great things about improving the emotional intelligence of an existing workforce is that you don’t only help your aged care workers demonstrate better emotional care with their clients and residents. You also help them become a better parent, partner, sibling and friend.

The skills of emotional intelligence include things like self-awareness, empathy, self-management and the capacity to positively influence the way others feel. Improving these things within yourself helps you improve your relationships at work, home and play.

Dr Ben Palmer is the CEO of Genos International. He designed the first Australian model and measure of emotional intelligence in the late 1990s, used in over 33 countries around the world in 28 different languages. He holds a PhD in Psychology from Swinburne University and is an Adjunct Professor with Torrens University in South Australia.

Do you have an idea for a story?Email [email protected]

Aged Care Insite Australia's number one aged care news source

Aged Care Insite Australia's number one aged care news source

Dear Dr Palmer

This seems logical. I assume it’s the same logic argued for the other end of life – those 0-8 years, where I assume emotion is more a driver than reasoning for learning and well-being.

So given that, I assume the Training Package for the Certificate III in Individual Support covers this off?

It would seem a logical preventive health strategy that comes at near zero cost to governments.

Ronald Jackson